“I’m an asshole. I’m abrasive. I am so sure that I’m right about virtually everything. I can sing you an aria of reasons to not like me,” says comics writer Christopher Priest, his bass voice rising to the brink of anger but never quite tipping over. “Not liking me because I’m black is so juvenile and immature, because there’s many reasons to not like me.” He’s speaking, as he often does, about the racism — both overt and structural — that he’s faced in the comics industry over his 40-year career. But that set of attributes, seen from another angle, can apply to the reasons to like him, or at least admire him — he’s unwaveringly outspoken, endearingly opinionated, as well as a pioneer in the comics industry. He’s also likely the only comics writer to have taken breaks from his career at various times to toil as a musician, pastor, and bus driver.

Priest, who’s 56, is about to see some of his most influential work go wide in a major way. His turn-of-the-millennium run at Marvel Comics, when he was writing the character Black Panther, has served as an inspiration for this year’s feverishly anticipated Marvel Studios film Black Panther. Given the comics world’s self-image of liberal inclusivity, and the fact that Priest is the first black writer to work full time at either Marvel or DC, starting with his first regular writing gig back in 1983, you might think he is long established as an elder statesman of the industry.

But until recently, Priest had bounced from job to job (including the aforementioned bus driving) and was largely denied the recognition he deserves. Indeed, talk to comics historians and they’ll have to pause for a minute and think before they conclude that, yes, he probably was the first African-American writer to truly break that barrier in superhero comics. Even among fervent fans, his milestones are far from common knowledge. He’d worked in quasi-obscurity for three decades before angrily retiring in 2005, opting to pursue work as a man of God in Colorado.

During that period of self-imposed exile, though, something happened, something Priest himself finds curious: He not only became recognized; he became a kind of icon. His run on Black Panther now merits its own multivolume reprint, Black Panther by Christopher Priest: The Complete Collection. He has reentered the spotlight, returning to Marvel — a place with which he has had a contentious relationship, to say the least — to write a new title, as well as taking on DC’s flagship team-up series, Justice League. To his surprise, he finds that crowds now pack convention halls to see him speak.

At a moment when Marvel Studios is making a self-consciously bold statement on inclusivity with Black Panther, Priest’s breaking of a color line deserves to finally be acknowledged. While Priest did not invent the Black Panther character — a superhero and king of a fictional African nation who had been kicking around Marvel for decades — in many ways he revolutionized it.

“He had the classic run on Black Panther, period, and that’s gonna be true for a long time,” says Ta-Nehisi Coates, who currently writes Black Panther for Marvel. “People had not put as much thought into who and what Black Panther was before Christopher started writing the book.” While previously the Panther had been written as a superhero, Coates notes, “[Priest] thought that Black Panther was a king.” It seems doubtful there’d even be a movie about him today if not for Priest’s refurbishing. Yet Priest himself has been chronically underappreciated.

Priest is nothing if not candid about his own career and the industry as a whole. In interviews and copious self-published essays, he speaks fiercely about injustices in comics, naming names and pointing fingers at people responsible for failures he thinks have been undeservedly ascribed to him. You might say that’s just a case of his being, to use his words, an asshole, but he’s frank about his own shortcomings and poor decisions. Still, he sees his predicament as part of a larger pattern. “When I read these self-congratulatory histories of Marvel and DC, they completely omit not just me but other persons of color or firsts,” he tells me. “Who was the first woman editor? Who was the first woman penciler? And I think part of it is that the people who were assembling these histories of it just didn’t think it was important. But these things do count, and they really do matter.”

Priest has not always been Christopher Priest — he grew up poor in the Hollis neighborhood of Queens and, back then, his name was James Christopher Owsley. Young James was, to put it indelicately, a dweeb. And the kids in his neighborhood weren’t very fond of dweebs. “It was a fairly hostile environment,” Priest recalls. “I got beat up a lot in that environment. I was mugged in that environment. I had guns pointed at me in anger in that environment.” Later in life, he’d write about lower-class black urban life — which he remembers unromantically. “I’d climb into the closet and just close the door and cup my hands over my ears and try to scream out this noise and just cry and go, ‘I hate being poor. I can’t stand being poor.’ ”

But the closet also brought a kind of aesthetic solace for young James. “I’d go in there and I’d read comics,” he says. “It was a big storage area, and I would climb in there, and I would put on a little lamp, and that was the only place I could get away from the maniacs.” He started out perusing DC, then moved on to Marvel, and he became an obsessive reader and collector. He dreamed of working at the latter of those two publishing giants, and during high school he began an internship there in 1978 — something no black person had ever done.

Before we go further, we should note that Priest was not the first black person to work in comics as a whole. Though small, there had been a tradition of African-American and mixed-race people having gigs in the industry, stretching from Krazy Kat cartoonist George Herriman in the early part of the 20th century; through Jackie Ormes, a black woman who drew terrific strips for the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier from the ’30s to the ’50s; to sci-fi writer Samuel R. Delany, who did bits of comics writing here and there; and Marvel artist Billy Graham, who helped shape the character Luke Cage in the early ’70s and occasionally helped out with some writing duties. Their contributions should not be understated.

However, the fact remains that no black people had been full-time comics writers or editors at the so-called Big Two of Marvel or DC until Priest entered the scene. The editor-in-chief of Marvel at the time, a stubborn and revolutionary leader named Jim Shooter, tells me he didn’t even notice that the office had been lily-white prior to Priest’s arrival. As for Priest, Shooter has nothing but praise. “He was crazy, high energy, and did everything you could ever ask of him,” Shooter says. “He started to wear roller skates so he could go back and forth on the floor. He was a really great kid and loved being there with all these creative people.”

Priest soon secured a gig as an assistant editor and became a full editor in 1984 at the tender age of 22. He also dipped his toe into writing: He penned a goofy one-off parody title called The Official Marvel No-Prize Book, then got a job writing a four-issue mini-series about longtime Captain America pal the Falcon, a black character. Then he was put on the long-running series Power Man and Iron Fist. He could do action with the best of them, but he was better at mixing humor and social commentary than anyone in the business at the time.

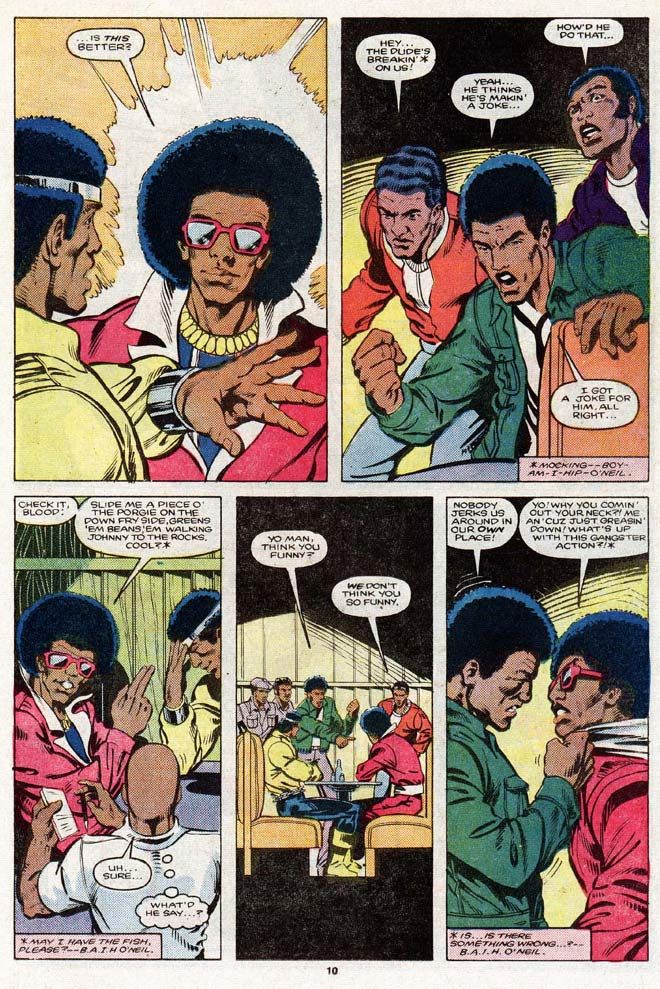

There’s a splendid scene in issue No. 121 of Power Man and Iron Fistwhere Power Man — who is black — finds himself chaperoning a shape-shifting alien who appears in the form of a white man. The alien orders some collard greens at a Harlem restaurant, and some nearby black patrons crack up: “You dig my man? He say, ‘And perhaps some collard greens!’” To defuse the situation, the alien tries to fit in by transforming into a jive-talking black man with an enormous ’fro, much to the patrons’ shock and disgust. “Check it, blood! Slide me a piece o’ the porgie on the down fry side, greens ’em beans!” the alien shouts earnestly. The patron grabs him by the collar. “You’re not funny, white man.” Few in mainstream comics were doing comedy this envelope pushing.

Unfortunately, Priest wasn’t as successful when he wasn’t holding the writer’s pen. His tenure as an editor was a disaster. “He wasn’t good at that,” Shooter recalls with a laugh. “He’s obviously a smart guy, but just had no interest in bureaucracy and wasn’t dealing real well with getting people to work on time and keeping a schedule and all that stuff.” His status as the only black editor made him a figure of inspiration and kinship for black freelance creators, which spurred some of his white co-workers to charge that he was coordinating some kind of African-American conspiracy. Priest responded by writing an open memo headlined “MARVEL WHITE SUPREMACY MEMO” identifying all the black creators he worked with and exactly why each one was present in the office.

“It was a terribly unhappy time of my life, both personally and professionally,” Priest later wrote of those years. He was put in charge of the Spider-Man titles, which he says was “an incredibly bad call. Saddling me with several beloved staffers as creative talent on books that constituted over $2 million of Marvel’s bottom line was a very bad idea.” He got into acrimonious fights with the writer-artist team on the lead Spidey title, Tom DeFalco and Ron Frenz, fights so bad that DeFalco and Frenz would later create what seemed to be a thinly veiled parody of Priest (who was then going by Jim Owsley) named Aloysius Jamesly, a flashy and delusional architect who refuses to heed the critiques of his builders and declares, “Don’t bother me with such petty details! I am a genius! An artist! This building will be my masterpiece!” “And our nightmare,” whispers one of the employees.

Eventually, recalls Shooter, “I called him into my office and said, ‘I have to fire you,’ and he said, ‘Thank you.’ ” Priest continued writing, even as Shooter was ousted from the company, removing his final quasi-friend. After penning a hit 1987 story called Spider-Man vs. Wolverine, he wasn’t asked to do a sequel — something Priest suspects had to do with racism. “That bothered me more than anything else,” he says. “That’s where I realized, Okay, yeah, I’m a black guy. Not just a black guy, but I’m really not well-liked up there.” He published his final Marvel script and moved over to DC Comics to work on a few titles, but grew frustrated when he was put through what he saw as too many rewrites of the first issue of a series called Emerald Dawn. Pissed off yet again, Priest chose to go into exile and, as he recalls, “settled into a quiet life far, far away, driving big Greyhound-style buses for Suburban Transit in North Brunswick, New Jersey.”

During this period, Priest entered the sights of DC editor Mike Gold. A political radical who had once worked on the defense of the Chicago Seven as a media coordinator and had done extensive work with low-income residents of that city’s Cabrini-Green housing projects, Gold cared deeply about the lack of black representation in the comics industry. “It was difficult to hire any black person back then, because it was an old white-boys’ club. You’d get a lot of questions like ‘Why do you want him? Boy, I hear he’s not reliable,’ ” Gold says. Gold admired Priest’s work at Marvel for its cleverness and edge, so he reached out in an effort to bring Priest in from the cold and make him an editor. Priest initially declined, but Gold was persistent.

Priest eventually took the gig in 1990 but kept his bus driver’s job as a backup. He raised eyebrows for putting up a poster of a gun-toting Malcolm X over his desk. It was during this period that he started going by Christopher Priest, to the confusion of his co-workers. Priest would later write, in an odd, third-person bio on his website, “He never discusses the true reasons behind his name change but insists every story you may have heard about it is absolutely true.” (Asked about it now, he says the name change, which came after his divorce, was because he wanted a more distinctive moniker.) Then the wheels came off of his DC run when he became infuriated with various editorial disputes over a title called Xero that left him feeling the company only had “callous disregard and contempt” for the book — and, one infers, for him. He left DC for nearly 20 years.

Luckily for whatever cult fan base Priest may have attracted, his finest work to date began just as his time at DC was crashing and burning. As the century ended, Priest wrote two series that are his greatest legacies: Quantum and Woody and Black Panther. The former was a project with artist M.D. Bright for a short-lived publisher called Acclaim Comics, a buddy-comedy about two men — one responsible and black, the other louche and white — who gain superpowers that require them to meet every 24 hours.

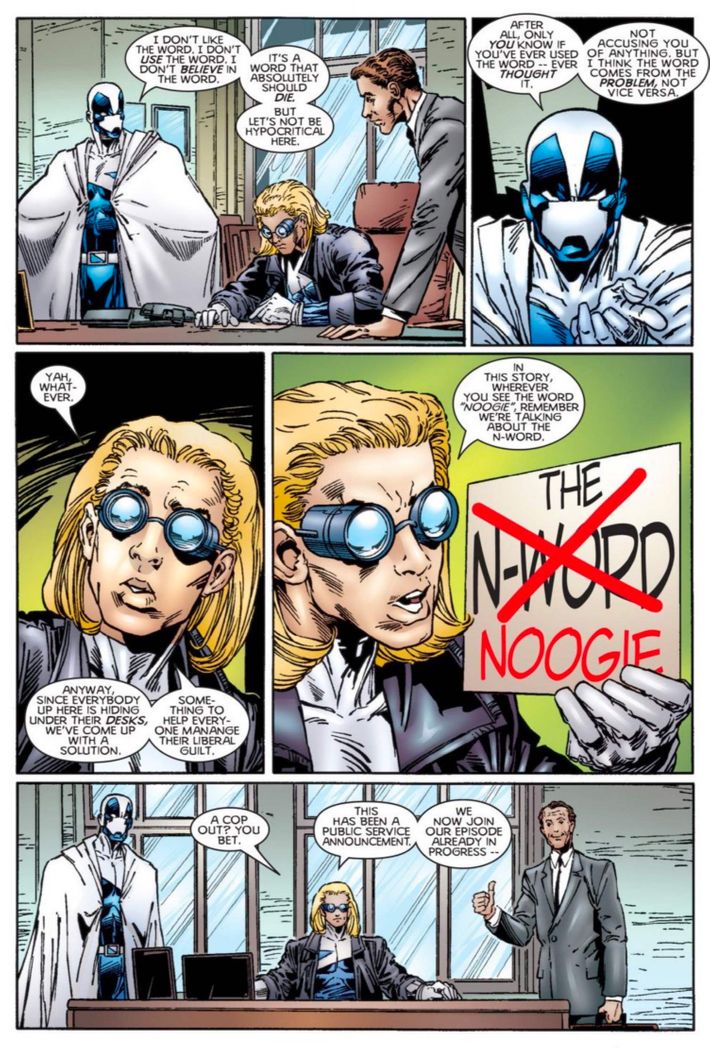

Told in nonlinear fashion, it was a delightful challenge to read: Details were withheld, recollections were unreliable, and jokes often required a detailed memory of what had gone before. In Priest’s mind, it was a “dysfunctional Batman and Robin starring Eriq La Salle (the nearly postal Dr. Benton from ER) and Woody Harrelson (reprising his character from White Men Can’t Jump and Money Train),” as he put it in an essay. As was becoming even more typical of Priest, it dared to poke at race in a way no one else was in the medium back then, playing with hand grenades like the N-word and the intersection of skin color and social class. It was a comics-lover’s comic, never quite moving the needle in sales, yet perpetually spoken of in reverent tones by critics and jaded geeks.

But the big action came when Priest made his unlikely, prodigal return to an old disaster site: Marvel Comics. By 1998, Marvel was in a financial tailspin and furiously tossing out new ideas. One such project was the Marvel Knights imprint, a stab at telling edgier stories about classic characters. Among them was Black Panther — a character that Knights editors Joe Quesada and Jimmy Palmiotti thought had potential. When they approached Priest about writing it, he was less than enthused.

“I was a little horrified when the words ‘Black’ and ‘Panther’ came out of Joe’s mouth,” he would later write. “I mean, Black Panther? Who reads Black Panther? Black Panther?!” But they were adamant, and Priest acquiesced — with “one basic stipulation: Black Panther could not be ‘a black book.’ ” Even though he had become the best interpreter of race in the game, Priest saw something troubling happening to his career. “I stopped being a writer, or being thought of as a writer,” he tells me, “and started being thought of as a blackwriter.”

So, in order to make this new endeavor interesting for himself, he managed to persuade Quesada and Palmiotti to let him give a book called Black Panther a white protagonist. While watching the Friendsepisode “The One With the Blackout,” Priest was taken by a scene in which Matthew Perry’s Chandler Bing finds himself trapped in an ATM vestibule with a supermodel. “Respected and successful, Bing nevertheless was the horrified fish out of water,” Priest later wrote. He felt he needed a Chandler, so he created Everett K. Ross, a hopelessly overwhelmed white man who works for the U.S. government and serves as a diplomatic escort for the Panther when the monarch embarks on a trip to Brooklyn. It was a genius move that allowed a book about a stoic superhero to be hilarious.

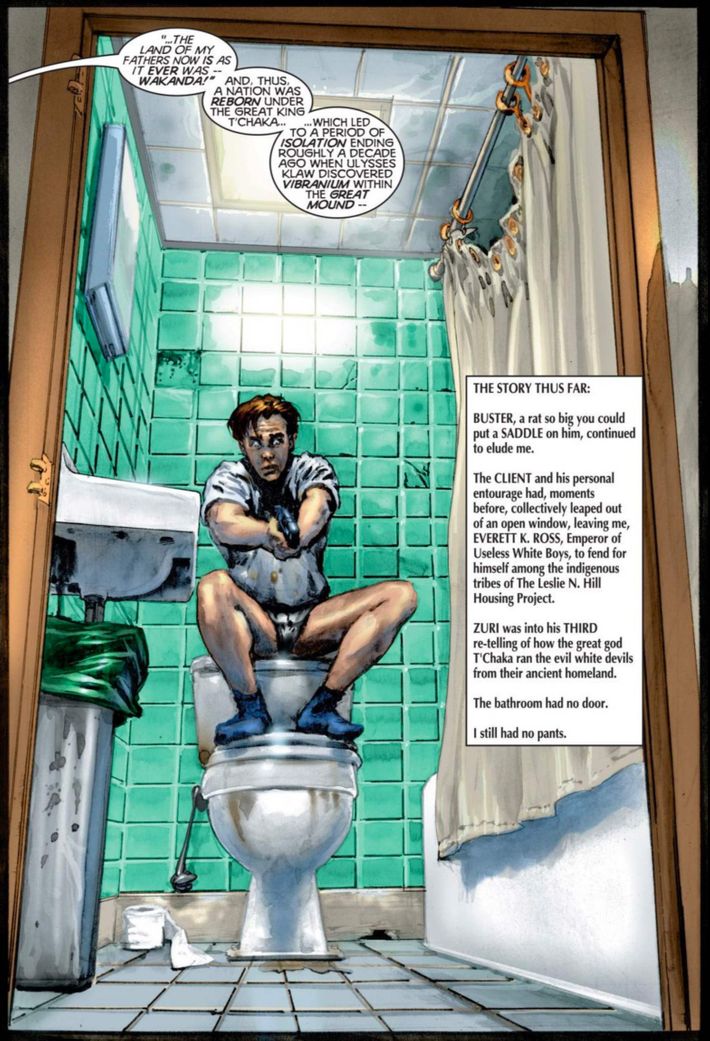

The first page of Priest’s Black Panther run, published in 1998, remains one of the best openings of any superhero epic. We see Ross huddled on a toilet in a grimy bathroom, wearing only a shirt, dress socks, and some tighty-whities; eyes wide, he’s pointing a gun toward the page’s bottom-right corner. “THE STORY THUS FAR,” Ross’s narration begins, throwing readers into a recitation about characters and terms with which the reader decidedly has no familiarity. “BUSTER, a rat so big you could put a SADDLE on him, continued to elude me. The CLIENT and his personal entourage had, moments before, collectively leaped out of an open window, leaving me, EVERETT K. ROSS, Emperor of Useless White Boys, to fend for himself among the indigenous tribes of The Leslie N. Hill Housing Project. ZURI was into his THIRD re-telling of how the great god T’Chaka ran the evil white devils out from their ancient homeland. The bathroom had no door. I still had no pants.”

The tone was set, and one of the great comic-book writing stretches had begun. The run lasted for 62 issues and is still the definitive take on the character. Nevertheless, Priest was once again dissatisfied with his treatment at Marvel. Black Panther ended, and a quasi-spinoff called The Crew was canceled after just seven issues in 2004. What’s more, Priest was exhausted after decades spent on the B- and C-lists, never writing a Superman or an Iron Man. “It felt like I just was wasting my time,” he tells me. “What’s the point? Everything I do gets canceled, and I’m never gonna be put on a top-tier book.” In 2005, he walked away from comics again — this time, it seemed, for good. Long a religious man, Priest, somewhat appropriately given his name, became a pastor and started a website about religion called praisenet.org. He did web-design work for various churches in Colorado, where he lives. A longtime musician, he played at worship services. “To be perfectly blunt, I think I was probably happier doing that than writing comics,” he says.

But he wants to be clear on something: Even though he stopped pitching comics, he was still open to writing them. He was just peeved about what he would periodically be asked to write. “Every 18 months, I’d get a call from Marvel or DC and they’d say, ‘Hey. We’re bringing back All-Negro Comics and we want you to write it.’ ‘We want you to do Black Goliath.’ ‘We want you to do Black Lightning,’ ” he says. He did a five-issue Quantum and Woody revival at Acclaim’s successor company, Valiant, in 2014, but remained estranged from the Big Two.

Then, something remarkable happened: Priest was offered Deathstroke the Terminator, a DC character. “My first question was ‘Is he black these days?’ They said, ‘No, he’s still a white guy.’ And I went, ‘Okay, I’m listening.’ ”

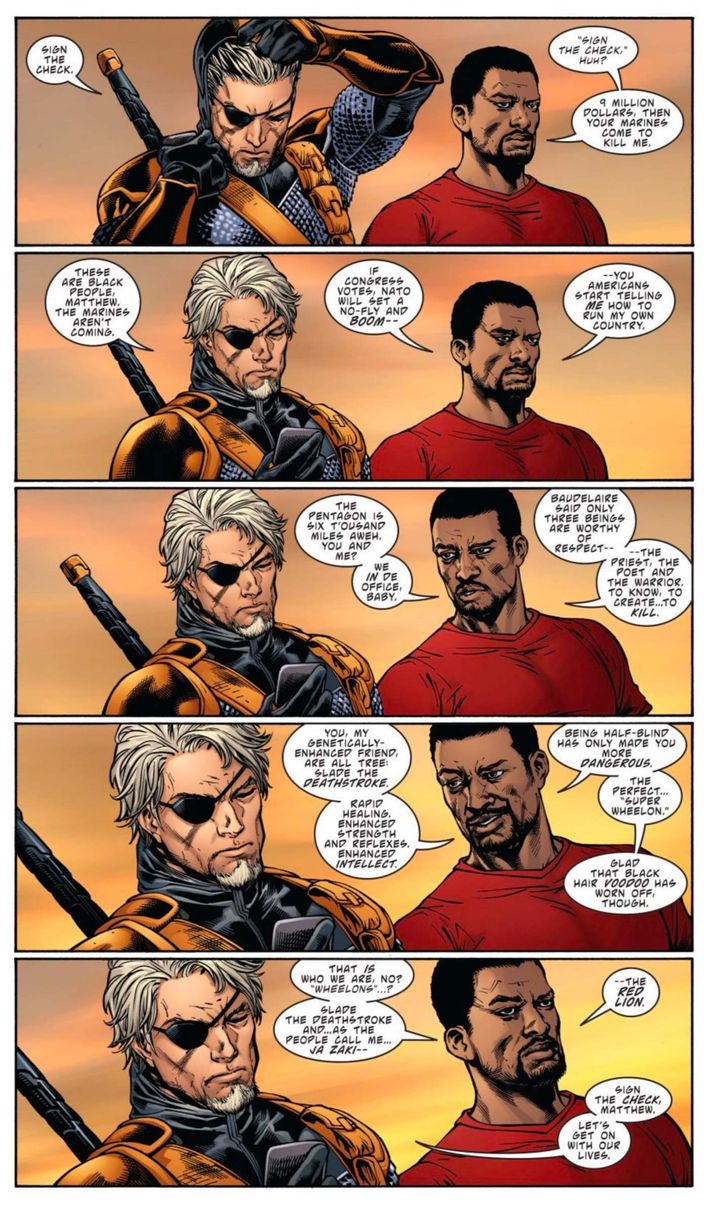

Priest agreed to write a new series, Deathstroke, as part of a DC initiative called Rebirth. When the lineup for Rebirth was announced, industry-watchers scanned them and found themselves surprised to see the name of Priest included on a mainstream book. They were not disappointed when the title began publishing. It’s consistently been one of the company’s best series, filled with popping action and — yes — interesting commentary on race. In the first issue, Deathstroke, a mercenary, stands above a pile of dead bodies in an African country alongside a local warlord. The warlord says he thinks America might send in Marines to stop the ongoing conflict in the region. “These are black people, Matthew,” Deathstroke tells him. “The Marines aren’t coming.”

Priest’s career has been on an upswing ever since. Aside from the attention to his work on Black Panther, he’s in the middle of a Justice League run that finally allows him to do what he always wanted: play with Superman, Batman, Wonder Woman, and more of DC’s most valuable toys. Last year, he helped launch a new superhero universefor indie publisher Lion Forge. Most surprisingly, Priest also returned to working with Marvel Comics with a just-concluded series about the long-running characters the Inhumans. As he put it in an interviewabout that last project: “I was a little shell-shocked at how easy the handshake was.”

If there’s one thing to learn from his odd career trajectory, it appears that comics need Priest more than Priest needs comics, so it’ll be interesting to see how long he sticks around this time. His absence would be a shame, if for no other reason than the fact that he’s already been so absent — not just as a writer but as a historical figure worth recognizing and reckoning with. “I’m a little insane, and I’m going to be a little different,” he says. “But hopefully, somewhere in there, in that creative arena, something will emerge that is new, and different, and unique.”

Recent Comments